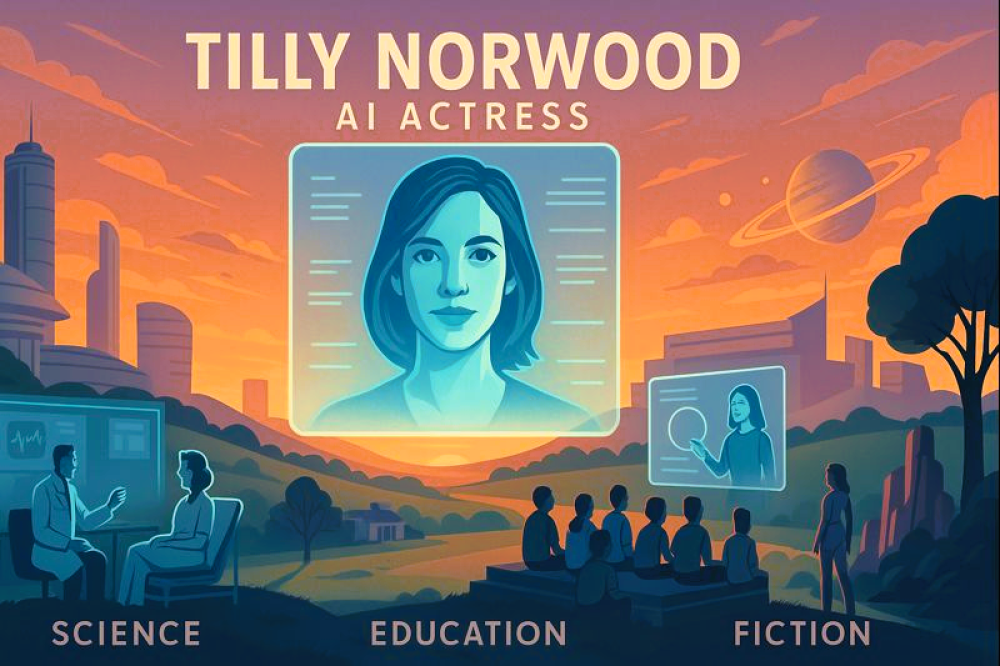

234/25 Tilly Norwood - A Pretty AI Actress: The Digital Human Shaping the Future of Science, Education, and Storytelling

Posted 1 month ago

She doesn’t breathe, age, or miss a beat. Yet, in 2025, Tilly Norwood, an entirely synthetic “actress,” became a focal point in Hollywood’s anxieties and a symbol of the broader conversation about the future of science, education, and storytelling, capturing reader interest from the start.

How have Digital Humans been Built?

Created by Dutch producer Eline Van der Velden by AI division Xicoia, Tilly Norwood is a hyper-real digital character built from a stack of generative tools: image models, 3D facial rigs, animation systems, and AI voice software. Thousands of visual and behavioural iterations were reportedly tested before her “final” look emerged, a friendly, conventionally attractive “girl next door” who lives on Instagram and in AI-generated sketches.

Whatever one thinks of her, Tilly is more than a publicity stunt. She is a prototype for a world in which believable digital people become routine. And that has profound implications far beyond Hollywood.

A Laboratory for Digital Humans

Tilly is a public-facing experiment in digital human technology. Scientists in the future will be able to use the same techniques used to make her smile, cry on cue, or stand on a red carpet, which can be repurposed in scientific and medical research.

Imagine “actors” like Tilly portraying virtual patients in simulated hospitals, reacting realistically to symptoms, treatments, and conversations with trainee doctors and nurses. For example, an AI patient could simulate a rare emergency, allowing clinicians to rehearse procedures safely and effectively, which highlights practical applications.

In neuroscience and psychology, AI characters may become standard tools for studying human interaction. Tilly can be reset infinitely, exposed to different social scenarios, and analysed for how people respond to her expressions, accents, or micro-gestures. Early experiments with robots and simple avatars already show that humans strongly project feelings onto artificial agents; high-fidelity characters like Tilly will make this effect much more powerful and measurable.

The Classroom with an Infinite Cast

Education is likely where Tilly’s descendants will be most visible, most quickly.

Today’s students already meet virtual assistants in language apps and LMS chatbots. Tomorrow, they may log into physics class and be welcomed not by a disembodied text box but by a stable cast of AI “teachers” and “historical guests”—each as visually coherent as Tilly, each capable of speaking dozens of languages and adjusting explanations to a child’s age and background.

Picture a history lesson where an AI “Marie Curie” and an AI “Tilly Norwood” co-present: Curie explains radiation experiments, while Tilly plays the curious journalist, asking the questions a hesitant teenager might be too shy to voice. In a biology class, an AI actor could literally step into the bloodstream, narrating from within a 3D-rendered body as immune cells swarm around her. With cinematic-grade avatars, lecture videos turn into scenes, and scenes can be paused, rewound, or re-imagined on demand.

For remote and under-resourced communities, AI actors could fill gaps left by the scarcity of specialist teachers. A school might not find a French language instructor willing to live in a rural town, but a convincing virtual mentor could appear at any hour, on any device, for any number of students.

Yet here too, Tilly’s existence forces hard questions:

• Who writes the scripts for these AI “teachers”?

• Which cultures, accents, and body types get encoded as “authoritative”?

• How do we prevent a subtle homogenisation of global education, in which millions of students grow up learning from the same small handful of cheerful, flawless, eternally 25-year-old faces?

Used wisely, AI actors could help personalise learning and make abstract topics feel alive. Used lazily, they could become glossy delivery mechanisms for shallow content, or tools for governments and corporations to push convenient narratives with charismatic, tireless digital spokespeople.

Fiction Beyond the Human Actor

In science fiction specifically, digital actors enable the visualisation of futures that were previously too expensive or technically challenging, such as alien civilisations with thousands of unique faces. In these time-travel narratives, a character meets many versions of themselves, or speculative biographies of thinkers who never lived.

But the more fluidly AI actors move between realities, the more we’ll need transparency-clear labels, watermarks, and media literacy-to build trust and confidence in the audience, ensuring they can distinguish between genuine and fictional performances.

Labour, Rights and the Shadow Cast

The backlash to Tilly Norwood has made one thing obvious: technology does not arrive in a vacuum. It steps onto a stage crowded with existing injustices, fears, and fragile livelihoods.

Human performers worry—reasonably—that studios will be tempted to scan their faces, train models on their performances, and then reuse their “essence” without paying them fairly. Unions have already argued that characters like Tilly are built on the unpaid labour and data of countless actors whose work forms the training set.

There are also thorny questions of likeness rights. Several people have publicly claimed that Tilly resembles them so closely that they feel their likeness was used without consent. In a world of near-perfect generative models, determining how different a digital face must be to be legally and ethically distinct remains a complex challenge, with laws still catching up.

A Mirror, Not a Replacement

Ultimately, Tilly Norwood is less a rival to human actors than a mirror held up to our systems.

Ultimately, Tilly Norwood is less a rival to human actors than a mirror held up to our systems, emphasizing that society can guide AI's development and regulation, fostering hope and reassurance for the audience.

For now, she stands at a strange frontier: a smiling, meticulously engineered reminder that the future of science, education, and fiction will be populated not just by humans looking at screens—but by the faces on those screens looking back.