229/25 An Entrepreneurial University

Posted 2 months ago

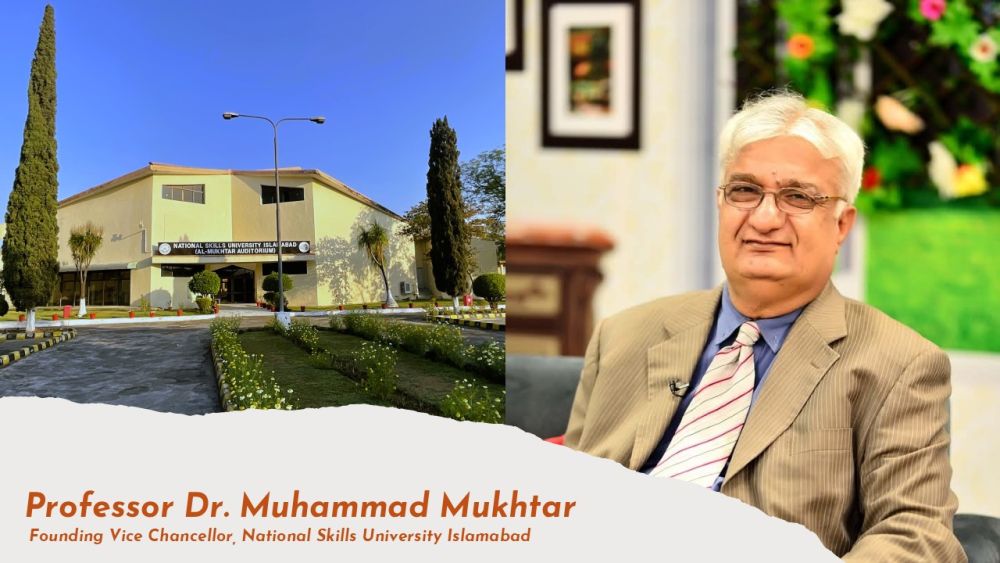

A Thought Provoking article by a visionary academic Leader

Professor Dr. Atta-ur-Rahman FRS, N.I., H.I., S.I., T.I.

Universities can turn students into job creators rather than job seekers, but only if they radically rethink how they teach. Around the world, the most entrepreneurial universities no longer treat entrepreneurship as a single elective; they embed it as a way of thinking, working, and living throughout the entire student experience.

1. Why universities must move from “job preparation” to “venture creation”

For most of the 20th century, universities were designed to supply talent for governments, large corporations, and professions such as medicine, law, and engineering. Success meant getting a “good job”. Today, however, automation, artificial intelligence, global competition, and platform economies are disrupting traditional employment pathways. Lifetime jobs are disappearing; project-based, freelance, and startup-driven work is expanding.

In such environments, students who graduate only with theoretical knowledge and rote learning are at a disadvantage. By contrast, those who know how to identify opportunities, assemble teams, validate ideas quickly, manage risk, and build organizations can create their own employment and jobs for others. Entrepreneurship is thus not merely about starting companies; it is about cultivating the ability to recognize opportunities, be creative, be resilient, and mobilize resources under uncertainty.

The central question becomes: how can universities deliberately train these capabilities, rather than assuming they will somehow emerge spontaneously?

2. Principles of cutting-edge entrepreneurship education

Around the world, leading institutions have converged on several shared principles:

2.1 Experiential, not purely theoretical. Students must try to build things prototypes, business models, and real ventures, not just read about them.

2.2 Customer- and problem-centric. Instead of starting with a technology or idea, students learn to start from a real user problem and then iterate solutions (design thinking, lean startup).

2.3 Interdisciplinary teams. Modern ventures rarely fit neatly into one discipline. Successful programs mix engineers, business students, designers, and social scientists.

2.4 Iteration and fast feedback. Students are encouraged to test ideas in the real world, fail quickly and cheaply, and learn from data.

2.5 Mentorship and ecosystem integration. Entrepreneurs learn faster when they are embedded in an ecosystem of founders, investors, incubators, and corporations.

2.6 Entrepreneurial mindset as a transversal skill. Even those who never start a company still benefit from the mindset in any career—public policy, NGOs, research, or large firms.

These principles translate into concrete methodologies: design thinking, lean startup, project-based learning, startup studios, venture accelerators, co-op placements in startups, and global immersion programmes.

3. Designing the curriculum: from lectures to venture laboratories

3.1 Foundational courses that teach how to think like an entrepreneur

A modern entrepreneurial curriculum usually begins with one or more foundation courses open to all students, regardless of major. Such courses should:

- Introduce opportunity recognition, business model design, basic finance, and intellectual property.

- Train students to conduct problem interviews, observe users, and map pain points.

- Use case studies of local and global startups, emphasizing not just success stories but also failures and pivots.

- Include small practical assignments: for example, identify a campus problem, interview 10 users, propose three solution concepts.

Many universities now integrate design thinking into these early courses. Design thinking is an iterative process with stages such as empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test that helps teams understand users and generate innovative solutions. “Design thinking is a non-linear, iterative process that teams use to understand users, challenge assumptions, redefine problems and create innovative solutions to prototype and test."

Evidence from empirical studies suggests that entrepreneurship courses using the Stanford d.school design thinking approach significantly improve students’ creativity and “entrepreneurial alertness” (their ability to notice and interpret opportunities).

3.2 Advanced venture creation courses

After foundational exposure, serious students can enter venture creation tracks where the “assignment” is to build a real startup over a semester or year. These courses typically:

- Require students to form interdisciplinary teams.

- Use the Lean Startup method: build–measure–learn cycles, minimum viable products, and customer validation.

- Integrate milestones: customer interviews completed, prototypes built, pilots run, revenue generated, or impact achieved.

- Replace traditional exams with demonstration days, investor pitches, and reflective learning journals.

Stanford Graduate School of Business, for example, offers a portfolio of entrepreneurship and innovation courses where students work with mentors, develop prototypes, and pitch to investors, often spinning ideas out into Silicon Valley startups.

3.3 Project-based learning across disciplines

Entrepreneurial thinking should not be confined to business schools. Engineering capstone projects, design studios, computer science projects, and even social science or public policy courses can be structured as problem-based projects with real stakeholders:

- Engineering students collaborate with local hospitals to design low-cost medical devices.

- Agricultural students work with farmers to test precision-agriculture tools.

- Humanities students develop cultural or creative-industry ventures.

Universities that do this well often create cross-listed courses and shared project studios where students from different faculties can work together.

4. Pedagogical methods that build entrepreneurial skills

4.1 Design thinking studios and makerspaces

Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design—the d.school—offers multidisciplinary studios where students learn through hands-on design challenges rather than lectures. The d.school describes itself as “a creative place where people use design to discover & build new possibilities”, offering university-wide electives and professional workshops.

Key features of this school include:

- Rapid prototyping with simple materials initially, then digital fabrication tools.

- Team-based projects with real external partners (companies, NGOs, government).

- An emphasis on empathy with users and iterative feedback.

Universities elsewhere can emulate this by investing in makerspaces, fab labs, and design studios accessible to all students, with technical staff and peer mentors.

4.2 Startup bootcamps and hackathons

Short, intense formats such as hackathons, startup weekends, and innovation bootcamps compress the entrepreneurial journey into 48 hours to a week:

- Students form teams around ideas.

- Mentors provide rapid feedback.

- Teams build prototypes and pitch at the end.

These events create emotional engagement and show students that it is possible to move from idea to prototype quickly. Aalto Entrepreneurship Society (Aaltoes) in Finland organizes over 100 events per year—including hackathons, pitching competitions, and networking events—drawing nearly 10,000 participants.

4.3 Learning through international immersion

Some of the most powerful entrepreneurship programmes send students into global startup hubs. The NUS Overseas Colleges (NOC) programme at the National University of Singapore is a leading example. NOC offers six to tweleve months internships in startups across more than 15–25 entrepreneurial hotspots (e.g., Silicon Valley, Beijing, New York), combined with entrepreneurship courses at partner universities.

Students work directly with founders, attend networking events, and are exposed to the culture of high-growth entrepreneurship. Many return to Singapore to start their own ventures, contributing to the country’s vibrant startup ecosystem.

Other universities, such as the Technical University of Munich (TUM), have partnered with NUS to create entrepreneurship exchange programmes that combine internships in Singaporean startups with academic coursework.

4.4 Incubators, accelerators, and startup studios inside universities

Beyond courses, universities can create incubation programmes where teams receive structured support over 6–18 months:

- Access to co-working space.

- Regular mentoring sessions with experienced entrepreneurs.

- Legal and accounting clinics.

- Small seed grants or competitions (proof-of-concept funding).

- Demo days to showcase to investors and corporate partners.

Tsinghua University’s x-lab is a good illustration: it is a university-based educational innovation platform that brings together students, faculty, alumni, entrepreneurs, investors, and experts to foster creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship. The x-lab offers multi-field courses, workshops, mentorship, and an Innovation & Entrepreneurship Certificate Programme, integrating practice with academic credit.

5. Building an entrepreneurial ecosystem on campus

Training individuals is necessary but not sufficient. Universities must also shape the ecosystem—the structures, policies, and culture that support entrepreneurial behaviour.

5.1 Student-run entrepreneurship societies

Student-driven organizations can be extraordinarily powerful. Aalto Entrepreneurship Society (Aaltoes), founded by Aalto University students in Finland, has become one of Europe’s largest and most active student-run entrepreneurship communities.

Aaltoes:

- Runs a 1,500 m² co-working space (“Startup Sauna”).

- Organizes over 100 events per year.

- Helped create major initiatives such as Slush (one of the world’s leading tech conferences), Junction (Europe’s leading hackathon), and startup accelerators like Kiuas.

This shows what can happen when universities empower students with space, modest funding, and autonomy.

5.2 Aligning university policies and incentives

To encourage entrepreneurship:

- IP policies should be clear and fair, allowing student and faculty founders to retain significant equity while sharing some returns with the university.

- Promotion and tenure criteria should recognize patents, spin-offs, and industry collaboration as valuable scholarly contributions.

- Administrative procedures for starting a company, licensing technology, or using university labs after graduation must be streamlined.

Some universities also allow students to take “entrepreneurial leave” to focus full-time on a startup while maintaining their enrolment status.

5.3 Linking with investors and corporates

Universities can host regular demo days, invite angel investors and venture capital funds, and set up co-innovation labs with corporations. Early customers and partners are often more important than early funding.

6. Training methods used by other countries: illustrative cases

6.1 United States: Stanford and Silicon Valley

The United States has many entrepreneurial universities, but Stanford is emblematic because of its deep integration with Silicon Valley.

Key practices include:

- A wide portfolio of entrepreneurship courses at the Graduate School of Business and across engineering and design, emphasizing experiential learning and real projects.

- The Stanford d.school, which has popularized design thinking worldwide through multidisciplinary, hands-on studios and professional workshops.

- Strong ties with alumni founders, venture capitalists, and technology companies, who regularly mentor and invest in student ventures.

- Encouraging students and faculty to take leaves of absence to pursue startups.

The pedagogical lesson: embed venture creation into the curriculum, and surround students with practitioners.

6.2 Singapore: National University of Singapore (NUS)

Singapore has deliberately positioned itself as a regional innovation hub. NUS plays a central role through NUS Enterprise and programmes like NUS Overseas Colleges (NOC) and MSc in Venture Creation.

- NOC sends students to more than 15–25 global entrepreneurial hotspots for long internships in startups, combined with entrepreneurship modules at partner universities.

- NUS Enterprise also runs summer programmes, incubators, and mentoring schemes that bring students into contact with founders and investors in Singapore’s dense startup ecosystem. NUS Enterprise+1

The lesson: international immersion and tight integration with national innovation policy can rapidly develop entrepreneurial talent.

6.3 China: Tsinghua University and x-lab

China has massively expanded entrepreneurship education across its universities as part of a national policy to move up the value chain. Tsinghua University’s x-lab is a flagship example:

- It is an interdisciplinary platform involving multiple schools (engineering, sciences, arts & design, economics, management, medicine, etc.) and external partners.

- Provides creativity and innovation courses, practical activities, workshops, and mentoring that lead to an Innovation & Entrepreneurship Certificate.

- Offers space, prototyping facilities, and access to investors.

The lesson: create a central innovation hub that connects all faculties and external stakeholders.

6.4 Finland: Aalto University and Aaltoes

Finland transformed itself from a resource-based economy into a high-tech, design-driven one partly through its startup ecosystem. Aalto University’s entrepreneurship ecosystem especially Aaltoes has been crucial:

- Aaltoes is funded by the university, government, and corporations and has an annual budget in the hundreds of thousands of euros, enabling large-scale events and support programmes.

- Student-led initiatives created Slush, now one of the world’s leading startup conferences, which in turn attracts global investors and partners to Helsinki.

The lesson: empowering students themselves to lead the entrepreneurial movement can change a country’s mindset toward risk-taking and innovation.

6.5 Other notable models

- Germany (TUM, KIT, etc.): strong entrepreneurship chairs, startup grants, and exchange programmes (e.g., the Entrepreneurship Exchange Programme with NUS).

- Israel: although not captured in the search above, it is widely documented that Israeli universities, together with military technology units and government programmes like Yozma, have created a dense startup ecosystem—illustrating the power of linking universities, government, and venture capital.

7. From theory to practice: concrete steps universities can take

To move from producing job-seekers to producing entrepreneurs, a university especially in a developing country—could implement the following roadmap.

7.1 Phase 1: Build foundations (1–2 years)

i. Audit current curriculum to identify where entrepreneurial mindsets, creativity, and problem-solving are (and are not) present.

ii. Introduce at least one university-wide introductory course in innovation and entrepreneurship, open to all students.

iii. Train faculty in modern pedagogies: design thinking, lean startup, and project-based learning (using open resources from institutions like the d.school).

iv. Establish a small entrepreneurship centre or office responsible for coordinating activities and connecting with external partners.

v. Create a student entrepreneurship club, giving it a modest budget, meeting space, and a staff liaison—planting the seed of an Aaltoes-like community.

7.2 Phase 2: Scale experiential learning (3–5 years)

a) Develop venture creation courses in multiple departments (engineering, business, computer science, agriculture, health sciences) with shared standards and mentor networks.

b) Launch annual innovation challenges focused on national or regional priorities (e.g., health, agriculture, fintech, climate adaptation).

c) Invest in a makerspace and prototyping lab accessible to students from all disciplines.

d) Formalize partnerships with local incubators, technology parks, chambers of commerce, and industry associations so student teams can test solutions in real settings.

e) Create a seed fund and proof-of-concept grants for student teams that meet certain milestones, with transparent selection processes.

7.3 Phase 3: Internationalization and ecosystem leadership (5–10 years)

A) Establish exchange programmes with global entrepreneurial universities, following the NUS Overseas Colleges and TUM–NUS models, where students work in startups abroad.

B) Host an annual startup summit or technology fair, inviting investors, corporates, and government agencies. Over time, such an event can grow into a regional Slush-type conference.

C) Create a university-affiliated accelerator that admits not only student teams but also startups from the broader community, enhancing the university’s role in national innovation.

D) Work with government and development agencies to align policy incentives (tax breaks, co-funding, innovation vouchers) with university entrepreneurship.

8. Cultivating the entrepreneurial mindset, not just skills

While tools like design thinking and lean startup are powerful, the most critical transformation is psychological and cultural.

8.1 Normalizing failure as learning

Traditional education often penalizes failure heavily. In entrepreneurship, failure is inevitable and often necessary for learning. Universities can:

- Encourage students to share “failure stories” in safe spaces.

- Incorporate graded reflections on what students learned from experiments that did not work.

- Feature alumni who failed in earlier ventures but later succeeded.

8.2 Encouraging ethical and impact-oriented entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship should not be equated simply with making money. Universities can emphasize ventures that address real societal and environmental challenges: clean energy, health access, education, agriculture, and inclusive fintech.

Elective modules in social entrepreneurship, impact investing, and sustainable business can sensitize students to these dimensions.

8.3 Inclusivity and gender balance

Special efforts are needed to support women, students from lower-income backgrounds, and under-represented groups:

- Targeted mentoring and role-model programmes.

- Childcare support for student parents.

- Micro-grants to cover early expenses that might otherwise be a barrier.

9. Measuring success and continuously improving

Universities must also take entrepreneurship education seriously enough to evaluate it rigorously:

- Track output metrics: number of student ventures, jobs created, revenue, investment raised, patents, social impact indicators.

- Track learning metrics: changes in entrepreneurial intention, risk tolerance, creativity, and opportunity recognition, as done in studies on design-thinking-based entrepreneurship education.

- Use feedback loops: regularly adjust courses, incubator programmes, and policies based on data and stakeholder input.

10. Conclusion

In a world of rapid technological change and economic uncertainty, universities that cling to a purely job-preparatory model will be a mega failure. The alternative is not vague encouragement to “be innovative”, but a deliberate, university-wide strategy to embed entrepreneurship in curricula, pedagogy, infrastructure, and culture.

International examples from Stanford’s d.school and entrepreneurship courses, to NUS Overseas Colleges’ global immersion, Tsinghua’s x-lab, and Aaltoes’ student-driven ecosystem—show that it is possible to transform both mindsets and economies by placing students at the centre of vibrant innovation communities.

If universities adopt experiential, interdisciplinary, design-driven, and ecosystem-connected approaches, students will not merely graduate with degrees; they will graduate with tested ideas, real networks, and the confidence to build organizations. They will pass out not as job seekers waiting for vacancies, but as entrepreneurs capable of creating value, employment, and solutions to some of the most pressing problems in their societies.

Scholarly Thoughts

Commenting on the above article former Executive Director of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) Pakistan Prof. Dr. Syed Sohail Naqvi says"

These good ideas cannot be pursued until the universities are given the space to explore new ideas in the curriculum. I am shocked that many curriculum approved by HEC contain absolutely NO room for the university to even offer one different course. This has to change before new ideas such as those of experiential learning of entrepreneurship can take hold.

Prof. Dr Javaid Laghari, Former Chairperson HEC believes that

HEC, and know how tedious and long it is with their governance structure to change policies. First recommendations by VC Committee, then setting up a task force, then taking their recommendations to the commission for approval.

HEC should only define guidelines, not a detailed curriculum. It should be upto each individual university to develop their own curriculum meeting the requirements of the accreditation bodies.

Further sharing his experiences in the United Arab Emirates Educaiton System Dr. Laghari comments:

I was the regulator for all UAE universities (over 100, with over 900 academic programs) as Commissioner for over 4 years. We were quite flexible in our approach, with the result that today UAE has the most enterprising universities of all in the whole region. They also have more universities in the top 500 of the world as compared to Pakistan. Khalifa University, American University of Sharjah, NYU at Abu Dhabi, and Masdar Institute are just a few examples of highly innovative universities.

The Dawood University of Engineering and Technology Vice Chancellor, Prof. Dr. Samreen Hussain sharing her experiences mentioned:

Agreed, at DUET we have also tried several strategies to stay aligned with our vision and mission statement, yet , setting up a curriculum for universities is hampering the intellectual development and creativity of faculty and leading to lethargic attitude and “ do as directed” sort of approach. College education and university education are different. There could be common bench marks but providing the complete recipe is causing monotony and making us brain dead somehow.

The regulators’ approach should be achieving a common goal of “ Graduates’ success” , with broader quality standards (well defined or tangibly applied) and best monitoring and evaluation process, and then leave it to HEI as to how they make it happen.

With a little disagreement to the suggestion of “ giving few universities “ , this leeway ; we must know that not every university can replicate them. Lab facilities are not same across the universities. Availability of HR to deliver that content is also a constraint. We need to carry on this conversation to reach out a win win situation for all without compromising basic quality parameters yet giving everyone the opportunity to work in their constraint resources and minimising the “ quality gap”.

Just a thought!

According to Engr. Prof. Dr. Arabella Bhutto in her experience of entreprenurial university:

Let me add that irrespective of these limitations, we at University of Sufism and Modern Sciences successfully managed to append 6 CHs of Sufi related courses to all disciplines. The approach opted is multidisciplinary and each department is now blending the concept of Sufism in their FYPs. In Education department we are working on Sufi Pedagogy. In Business we are working on Sufi Leadership and Ethics. In IT we are working on AI based videography. In English we are working on Sufi Dictionary to name a few. This approach may help us devising our indigenous curriculum and bring the expected change.

According to Prof. Dr. Rauf I Azam, Vice Chancellor of the GC University Faisalabad

But that is not happening.

I think over time and in the absence of meaningful direction or oversight by HEC the Curriculum Review Committees have encroached upon the authority of the universities and have adopted this dictatorial approach of issuing hard-coded curricula. Besides, some players other than the HEC and NCRCs have also adopted the approach of issuing directives to include certain elements into the university curricula which has consumed any flexibility that remained. Now it has become very hard for the universities to create and maintain any differentiation.

Professor Azam believes that with the new leadership taking up the responsibility at HEC we can hope for a correction of strategy and taking the right course. There's a lot to be corrected.